Septimal Mind Blog

August 2019 (4943 Words, 28 Minutes)

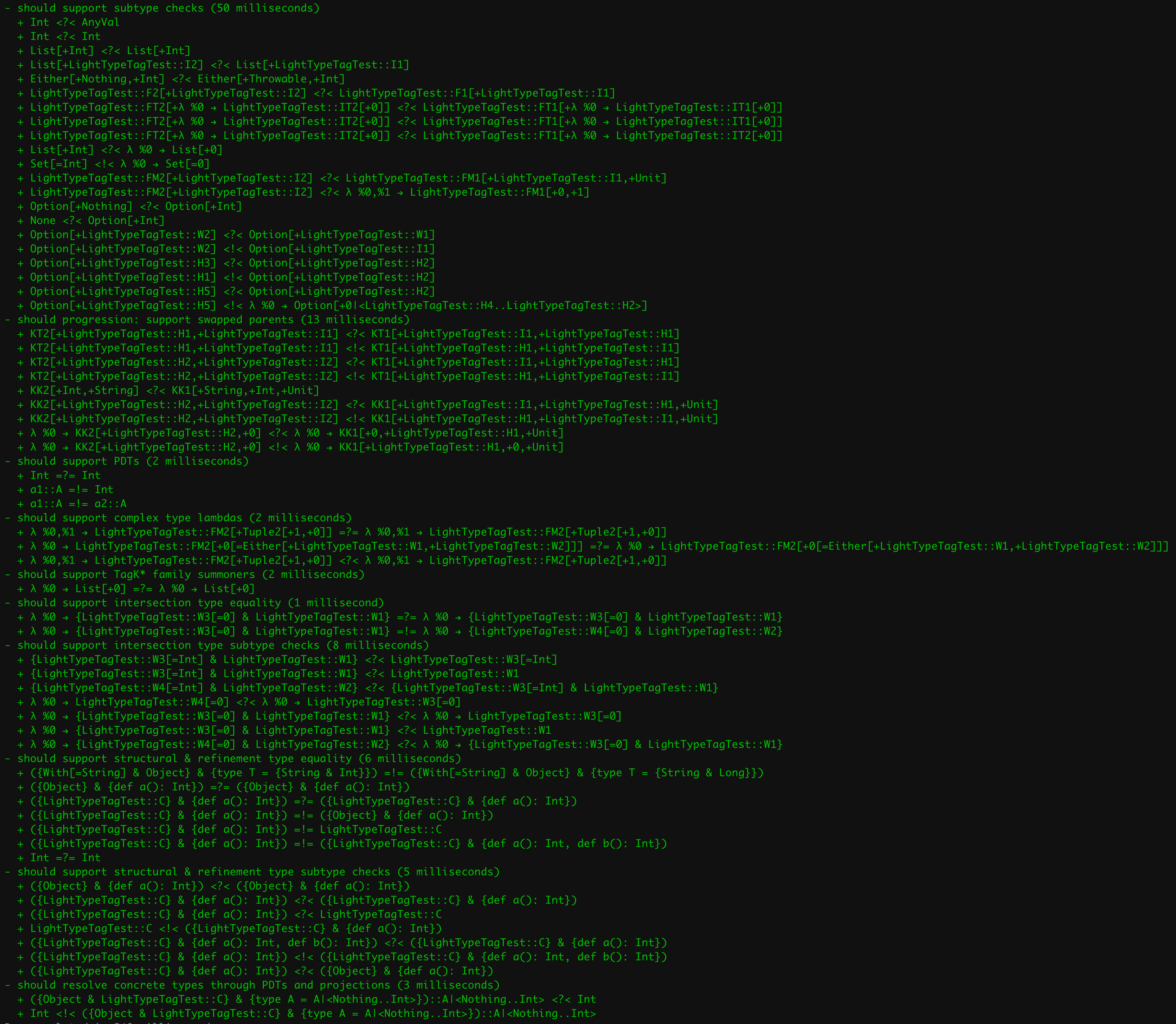

Lightweight Scala Reflection and why Dotty needs TypeTags reimplemented

Summary

TypeTag in scala-reflect is great but flawed. In this article I provide some observations of my experience of building

a custom type tag that does not depend on scala-reflect at runtime, is potentially portable to Dotty, and provides equality and subtype checks. Our usage scenario is: we generate type tags at compile time and check their equality and subtyping at runtime; we don’t use them to cast anything, and we don’t need to generate types at runtime. Our model is not completely correct, though it is enough for most purposes. I also hope this post may help convince the Dotty team to support some form of type tags. There is a corresponding ticket on the Dotty bug tracker and a discussion on the Scala Contributors list. This post targets those who have some knowledge of scala-reflect and are unhappy with it, those who have some knowledge of the Scala compiler and its APIs, and other nerds.

TLDR: usage example

Add this into your build.sbt:

libraryDependencies += "io.7mind.izumi" %% "fundamentals-reflection" % "0.9.5"

Then try the following (Scastie):

import izumi.fundamentals.reflection.macrortti._

import izumi.fundamentals.reflection.Tags._

// === === === === === === === === === //

def combinationTest() = {

val tag1 = TagK[List].tag

val tag2 = Tag[Int].tag

val tag3 = tag1.combine(tag2)

val tag4 = Tag[List[Int]].tag

println(s"list tag: $tag1, int tag: $tag2, combined: $tag3, combined tag is equal to List[Int] tag: ${tag3 =:= tag4}")

}

combinationTest()

// === === === === === === === === === //

type Id[K] = K

def subtypeTest() = {

case class Datum[F[_] : TagK](a: F[Int]) {

def tag: LightTypeTag = implicitly[TagK[F]].tag

}

val elements = List(

Datum[Id](1),

Datum[List](List(1,2,3))

)

val seqElements = elements.filter(_.tag <:< TagK[Seq].tag)

println(s"Only elements parameterized by Seq[_] children: $seqElements")

}

subtypeTest()

This example will produce the following output:

list tag: λ %0 → List[+0], int tag: Int, combined: List[+Int], combined tag is equal to List[Int] tag: true

Only elements parameterized by Seq[_] children: List(Datum(List(1, 2, 3)))

Introduction

Type tags are one of the most attractive features of Scala.

They allow you to overcome type erasure, check subtyping and equality. Here is an example:

import scala.reflect.runtime.universe._

def check[T : TypeTag](v: T) = {

val tag = implicitly[TypeTag[T]].tpe

println(s"//↳value $v is of type $tag")

if (tag =:= typeTag[Right[Int, Int]].tpe) {

println(s"//↳value $v has exact type of Right[Int, Int]")

}

if (tag <:< typeTag[Either[Int, Object]].tpe) {

println(s"//↳value $v is a subtype of Either[Int, Object]: $tag")

}

}

check(Right[Int, Int](1))

//↳value Right(1) is of type scala.util.Right[Int,Int]

//↳value Right(1) has exact type of Right[Int, Int]

check(Right[Nothing, Int](1))

//↳value Right(1) is of type scala.util.Right[Nothing,Int]

check(Right("xxx"))

//↳value Right(xxx) is of type scala.util.Right[Nothing,String]

//↳value Right(xxx) is a subtype of Either[Int, Object]: scala.util.Right[Nothing,String]

TypeTag lets you do a lot more. Essentially, scala-reflect and TypeTag machinery are chunks of internal compiler data structures and tools exposed directly to the user. Though the most important operations are equality check (=:=) and subtype check (<:<) — in case you have them you may implement whatever else you need at least semi-automatically.

The concept of a type tag is a cornerstone of our project — distage — a smart module system for Scala featuring a solver and a dependency injection mechanism.

Type tags allows us to turn an arbitrary function into an entity which may be introspected at both compile time and run time (Scastie):

import com.github.pshirshov.izumi.distage.model.providers.ProviderMagnet

val fn = ProviderMagnet {

(x: Int, y: String) => (x, y)

}.get

println(s"//↳function arity: ${fn.arity}")

//↳function arity: 2

println(s"//↳function signature: ${fn.argTypes}")

//↳function signature: List(Int, String)

println(s"//↳function return type: ${fn.ret}")

//↳function return type: (Int, String)

println(s"//↳function application: ${fn.fun.apply(Seq(1, "hi"))}")

//↳function application: (1,hi)

Unfortunately, current TypeTag implementation is flawed:

- They do not support higher-kinded types, you cannot get a

TypeTagforList[_], - They suffer from many concurrency issues — in our case, TypeTags were occasionally failing subtype checks (

child <:< parent) duringscala-reflectinitialization even if we synchronized on literally everything — and it’s not trivial to fix them; in the worst-case scenario you may even seeSet[Int]asSet[String], scala-reflectneeds seconds to initialize.

Moreover, it’s still unclear if Scala 3 will support TypeTags or not.

Some people say it’s too hard and recommend writing a custom macro to replace TypeTags in Scala 3 / Dotty when necessary.

So, we tried to implement our own lightweight TypeTag replacement with a macro.

The guys who work on Scala/Dotty compilers say that it’s a very complicated task:

A full implmentation of subtyping is extremely complex

Yikes but the full subtyping algorithm is extremely complex. And also carefull.

But it’s doable. We did it, and our model is good enough for many practical use cases despite being overcomplicated and having subtle discrepancies with the Scala model. So we still hope that the Dotty team will consider supporting TypeTags in Scala 3. Currently, our implementation supports Scala 2.12/2.13. It’s possible to port it to Dotty, and we are going to do that in the foreseeable future.

The scope of the work

The following features are essential for distage and very useful for many different purposes:

- An ability to combine type tags at runtime:

CustomTag[List[_]].combine(CustomTag[Int]) - An ability to check if two types are identical:

assert(CustomTag[List[Int]] =:= CustomTag[List].combine(CustomTag[Int])) - An ability to check if one type is a subtype of another:

assert(CustomTag[List[Int]] <:< CustomTag[List[Any]]) assert(CustomTag[Either[Nothing, ?]] <:< CustomTag[Either[Unit, ?]])

Starting point: undefined behavior in Scalac helps to circumvent TypeTag limitations

Unfortunately, there is no way in Scala to request a TypeTag for an unapplied type (or a “type lambda”). The model itself can express it but there is no syntax for that.

So, this doesn’t work:

type T[K] = Either[K, Unit]

typeTag[T] // fail

Fortunately there are two workarounds for that.

Undefined behavior for rescue: simple materializer

For some reason scalac ignores type parameters passed to a type within macro definition:

import scala.language.experimental.macros

import scala.reflect.macros.blackbox

import scala.reflect.runtime.universe._

trait LightTypeTag { /*TODO*/ }

def makeTag[T: c.WeakTypeTag](c: blackbox.Context): c.Expr[LightTypeTag] = {

import c.universe._

val tpe = implicitly[WeakTypeTag[T]].tpe

// etaExpand converts any type taking arguments into PolyTypeApi ---

// a type lambda representation

println(("type tag", tpe.etaExpand))

println(("unbound type parameters", tpe.typeParams))

println(("result type", tpe.etaExpand.resultType.dealias))

c.Expr[LightTypeTag](q"null")

}

def materialize1[T[_]]: LightTypeTag = macro makeTag[T[Nothing]]

type T0[K, V] = Either[K, V]

type T1[K1] = T0[K1, Unit]

materialize1[T1]

This example prints

(type tag,[K1]T1[K1])

(unbound type parameters,List(type K1))

(result type,scala.util.Either[K1,Unit])

It’s time to make some observations:

Nothinghas disappeared out ofT[Nothing],- Scala’s syntactic limitations were successfully circumvented and we got a weak type tag for our unapplied

type T1[K]! It’s an undefined but logical and very useful behaviour, - Scala can expand all the nested lambdas into a single lambda.

Better approach

Previous trick would require us to manually write a custom materializer for every kind we want to get our type tags for. So there is another approach which is more useful for practical usage.

Type lambda may be wrapped into a structural refinement of a type:

trait HKTag[T] {

// ...

}

type Wrapped[K[_]] = HKTag[{ type Arg[A] = K[A] }]

Now there are no more of those damn type arguments, and we may analyze different Wrapped types uniformly.

This is outside of the scope of this post, you may find completed and working example in distage repository

Designing data model

We want to use a macro to statically generate unambiguous type identifiers. The following Scala features have to be supported:

- Parameterized types (Generics),

- Unapplied types (type lambdas, higher-kinded types),

- Compound types:

val v: Type1 with Type2, - Structural types:

val v: {def repr(a: Int): String}, - Path-dependent types:

val a: b.T. Actually it’s very hard to provide comprehensive support for PDTs but it may be done to some extent — , - Variances:

trait T[+A], - Type bounds:

trait T1[K <: T0]

Essentially, there are two primary forms of the types, applied and unapplied. So, let’s encode this:

sealed trait LightTypeTag

sealed trait AppliedReference extends LightTypeTag

sealed trait AppliedNamedReference extends LightTypeTag

Now it’s possible to define helper structures, describing type bounds and variance:

sealed trait Boundaries

object Boundaries {

case class Defined(bottom: LightTypeTag, top: LightTypeTag) extends Boundaries

case object Empty extends Boundaries

}

sealed trait Variance

object Variance {

case object Invariant extends Variance

case object Contravariant extends Variance

case object Covariant extends Variance

}

Boundaries.Empty is just an optimization for default boundaries of >: Nothing <: Any intended to make generated tree more compact.

Gotcha: type bounds in Scala are recursive! So it’s pretty hard to restore them properly, but the recursion can be detected and the boundaries loosened appropriately.

Non-generic types may be identified by their fully qualified names. A type may have a prefix (in case it’s a PDT) and type boundaries (in case it’s an abstract type parameter):

case class NameReference(

ref: String,

boundaries: Boundaries,

prefix: Option[AppliedReference]

)extends AppliedNamedReference

It’s time for a generic type reference. It’s a recursive structure with an fully qualified type name and a list of arbitrary type tags representing generic arguments:

case class TypeParam(ref: LightTypeTag, variance: Variance)

case class FullReference(

ref: String,

parameters: List[TypeParam],

prefix: Option[AppliedReference]

) extends AppliedNamedReference

Now a type lambda may be defined:

case class Lambda(

input: List[LambdaParameter],

output: LightTypeTag

) extends LightTypeTag

case class LambdaParameter(name: String)

The compound type is simple:

case class IntersectionReference(refs: Set[AppliedNamedReference]) extends AppliedReference

And here comes structural type:

sealed trait RefinementDecl

object RefinementDecl {

case class Signature(

name: String,

input: List[AppliedReference],

output: AppliedReference

) extends RefinementDecl

case class TypeMember(

name: String,

ref: LightTypeTag

) extends RefinementDecl

}

case class Refinement(

reference: AppliedReference,

decls: Set[RefinementDecl]

) extends AppliedReference

There are many ways this model can be improved. For example it’s better to use a NonEmptyList in FullReference and Lambda, some prefixes, allowed by the model, are invalid, etc, etc.

Also there are some issues:

- Path-dependent types will use their names instead of

Though it does the job. Also it provides equality check for free in case the tags are being built in some kind of a normal form. I would be happy to get any improvement proposals.

The logic behind

In this section I will consider some caveats I faced and and design choices I made while working on my implementation.

Compile time: type lambdas and kind projector

Type lambdas are represented as PolyTypeApi. They always have empty typeArgs list and at least one element in typeParams list. Lambda result type may be accessed with .resultType.dealias methods.

Unfortunately, the following things require different approach

- type lambdas encoded with type projections,

- code produced by Kind Projector — a plugin, providing us a way to encode type lambdas in scala with sane syntax.

In both of the cases takesTypeArgs returns true but the types are not instances of PolyTypeApi. So it’s important to call etaExpand before processing the lambda.

Next thing is: result type of a type lambda is always an applied type. Lambda parameters are visible as concrete types there: for the following lambda: type L[A] = List[A] the result type would be List[A] where A is a “concrete” type.

So, before type lambda can be processed it’s argument names need to be recovered. Then the alghoritm should recurse into the result type substituting type parameters with corresponding lamda parameters.

An example:

def toPrefix(tpef: u.Type): Option[AppliedReference] = ???

def makeBoundaries(t: Type): Boundaries = ???

def toVariance(tpes: TypeSymbol): Variance = ???

def makeRef(tpe: Type, context: Map[String, LambdaParameter]): LightTypeTag = {

def makeLambda(t: Type): LightTypeTag = {

val asPoly = t.etaExpand

val result = asPoly.resultType.dealias

val lamParams = t.typeParams.zipWithIndex.map {

case (p, idx) =>

p.fullName -> LambdaParameter(idx.toString)

}

val reference = makeRef(result, lamParams.toMap)

Lambda(lamParams.map(_._2), reference)

}

def unpack(t: Type, context: Map[String, LambdaParameter]): AppliedNamedReference = {

val tpef = t.dealias.resultType

val prefix = toPrefix(tpef)

val typeSymbol = tpef.typeSymbol

val b = makeBoundaries(tpef)

val nameref = context.get(typeSymbol.fullName) match {

case Some(value) =>

NameReference(value.name, b, prefix)

case None =>

NameReference(typeSymbol.fullName, b, prefix)

}

tpef.typeArgs match {

case Nil =>

nameref

case args =>

val params = args.zip(t.dealias.typeConstructor.typeParams).map {

case (a, pa) =>

TypeParam(makeRef(a, context), toVariance(pa.asType))

}

FullReference(nameref.ref, params, prefix)

}

}

val out = tpe match {

case _: PolyTypeApi =>

makeLambda(tpe)

case p if p.takesTypeArgs =>

if (context.contains(p.typeSymbol.fullName)) {

unpack(p, context)

} else {

makeLambda(p)

}

case c =>

unpack(c, context)

}

out

}

An API allowing us to apply and partially apply a lambda is necessary for any runtime usage. This will be the cornerstoune of our type tag combinators:

def applyLambda(lambda: Lambda, parameters: Map[String, LightTypeTag]): LightTypeTag

This method should recursively replace all the references to lambda arguments with corresponding type references from parameters map. So apply(λ %0, %1 → Map[%0, %1], Int) becomes λ %0 → Map[Int, %0]. This job is mostly mechanical.

Compile time: refinement types

For some reason not all the refined types implement RefinedTypeApi. It’s necessary to use internal scalac structures not to miss something. Here is a working extractor:

import c._

final val it = universe.asInstanceOf[scala.reflect.internal.Types]

object RefinedType {

def unapply(tpef: Type): Option[(List[Type], List[SymbolApi])] = {

tpef.asInstanceOf[AnyRef] match {

case x: it.RefinementTypeRef =>

Some((

x.parents.map(_.asInstanceOf[Type]),

x.decls.map(_.asInstanceOf[SymbolApi]).toList

))

case r: RefinedTypeApi =>

Some((r.parents, r.decls.toList))

case _ =>

None

}

}

}

val t: Type = ???

t match {

case RefinedType(parents, decls) =>

//...

}

Runtime: subtype checks

Equality check is trivial — equals on our model instances would work just fine.

Subtype checking is somewhat complicated.

I wouldn’t discuss it in the detail here, you may refer to my actual implementation.

It’s hard to understand what is even needed to perform the check.

Right now I’m storing the following data:

val baseTypes: Map[LightTypeTag, Set[LightTypeTag]]

val baseNames: Map[NameReference, Set[NameReference]]

I use baseNames to compare NameReferences and baseTypes for all other things.

There is one caveat: scalac does not provide consistent representation for base types of unapplied types. So it’s not so easy to figure out that Seq[?] is a base type for List[?].

Fortunately the type names in the base type reference correspond to the names type parameters list:

import scala.language.experimental.macros

import scala.reflect.macros.blackbox

import scala.reflect.runtime.universe._

val tpe = typeTag[List[Int]].tpe.typeConstructor

// tpe is a type of a type lambda

val baseTypes = tpe.typeConstructor.baseClasses.map(t => tpe.baseType(t))

// all the elements of baseTypes are applied. `A` is a "concrete" type

// List(List[A], scala.collection.LinearSeqOps[A,[X]List[X],List[A]], Seq[A], ...)

// though type names will correspond to type arguments

val targs = tpe.etaExpand.typeParams

// fortunately type names are the same

// List[reflect.runtime.universe.Symbol] = List(type A)

So, each base type may be reconstructed by using type parameters to populate the context for makeRef.

The comparison alghoritm itself is a recursive procedure which considers all the possible pairs of type references plus some basic cornercases.

The primary cases are:

def isChild(selfT: LightTypeTag, thatT: LightTypeTag): Boolean = {

(selfT, thatT) match {

case (s, t) if s == t =>

true

case (s, _) if s == tpeNothing =>

true

case (_, t) if t == tpeAny || t == tpeAnyRef || t == tpeObject =>

true

case (s: FullReference, t: FullReference) =>

if (parentsOf(s.asName).contains(t)) {

true

} else {

oneOfKnownParentsIsInheritedFrom(ctx)(s, t) || compareParameterizedRefs(ctx)(s, t)

}

case (s: NameReference, t: FullReference) =>

oneOfKnownParentsIsInheritedFrom(ctx)(s, t)

case (s: NameReference, t: NameReference) =>

parentsOf(s).exists(p => isChild(p, thatT))

case (_: AppliedNamedReference, t: Lambda) =>

isChild(selfT, t.output)

case (s: Lambda, t: AppliedNamedReference) =>

isChild(s.output, t)

case (s: Lambda, o: Lambda) =>

s.input == o.input && isChild(s.output, o.output)

// ...

}

}

Several helper functions are required as well:

// uses `baseNames` to transitively fetch all parent type names

def parentsOf(t: NameReference): Set[NameReference] = ???

def oneOfKnownParentsIsInheritedFrom(child: LightTypeTag, parent: LightTypeTag): Boolean = {

baseTypes.get(t).toSeq.flatten.exists(p => isChild(p, parent))

}

def isSame(a: LightTypeTag, b: LightTypeTag): Boolean = {

(a, b) match {

case (an: AppliedNamedReference, ab: AppliedNamedReference) =>

an.asName == ab.asName

case _ =>

false

}

}

The trickiest part is the comparator for FullReferences:

def compareParameterizedRefs(self: FullReference, that: FullReference): Boolean = {

def parameterShapeCompatible: Boolean = {

self.parameters.zip(that.parameters).forall {

case (ps, pt) =>

ps.variance match {

case Variance.Invariant =>

ps.ref == pt.ref

case Variance.Contravariant =>

isChild(pt.ref, ps.ref)

case Variance.Covariant =>

isChild(ps.ref, pt.ref)

}

}

}

def sameArity: Boolean = {

self.parameters.size == that.parameters.size

}

if (self.asName == that.asName) {

sameArity && parameterShapeCompatible

} else if (isChild(self.asName, that.asName)) {

// we search for all the lambdas having potentially compatible result type

val moreParents = baseTypes

.collect {

case (l: Lambda, b) if isSame(l.output, self.asName) =>

b

.collect {

case l: Lambda if l.input.size == self.parameters.size => l

}

.map(l => l.combine(self.parameters.map(_.ref)))

}

.flatten

moreParents

.exists {

l =>

val maybeParent = l

isChild(maybeParent, that)

}

} else {

false

}

}

The real code is more complicated (it takes care of bound lambda parameters also), but this is the main idea.

In fact these are simple symbolic computations mocking the hard work of the Scala compiler. But they work.

The rest of the damn Owl

I provided some basic insights into the problem. In case you wish to look at the full implementation, you may find it in our repository. It has 2K+ LoC and has all the necessary features implemented. Also there are some logging facilities allowing you to get a detailed log of what happens during subtype checks.

We would welcome any contributions into our library and feel free to use this post and our code as a starting point for your own implementation.

Conclusion

It’s possible to implement scala-reflect-like features with a macro. Though it’s a challenging task.

At the same time for many enterprise developers good reflection is one of the most attractive Scala features.

It allows us to have many positive traits of dynamic languages without giving up on type safety.

I wrote this post in the hope that it may help convince the Dotty team to re-implement reflection in Scala 3. In case it wouldn’t, we, Septimal Mind will try to maintain our solution and port it to Dotty, but, as I mentioned earlier, it’s not possible to make it completely correct.