Septimal Mind Blog

November 2019 (1836 Words, 11 Minutes)

Unit, Functional, Integration? You are doing it wrong

Summary

Many engineers don’t pay enough attention to tests. There are two reasons for this: it’s hard to write good tests, and it’s not easy to formalize which tests are good and which are bad.

We created our own test taxonomy, an alternative to the classic Unit/Functional/Integration trinity, allowing engineers to establish useful guidelines for their work on test suites.

The problem

We all write tests. Most of us do it regularly. Many of us consider tests as important as our business logic is because tests establish important contracts and greatly reduce maintenance costs.

Not all tests are equal, though. Once we write them, we start noticing that some are helpful while others are troublesome.

We may say that bad tests are:

- Slow

- Unstable: they fail randomly

- Nonviable: don’t survive refactorings

- Demanding: require complex preconditions to be met: external services up and running, fixtures loaded, etc, etc

- Incomprehensible: they signal about a problem but don’t help us to localize the cause

Though the question is: how do we write better tests? How do we choose the best possible strategy when we start writing a test?

It’s surprisingly hard to answer that question and I think that one of the reasons for that is the fact that we… just miss proper vocabulary and improperly use the existing one.

We used to classify tests using words like “Unit”, “Functional”, and “Integration” (also “System”, “Performance”, and “Acceptance”). And we think something like: “unit tests are better than functional tests, and integration tests are the worst.” We also know that high coverage is good.

Usual definitions are:

- A unit test checks the functionality of individual modules or units.

- A functional test checks whether the system works according to the requirements.

- An integration test checks related programs, modules, or units of code.

Let’s assume we have a system with the following components:

ILoanCalculatorwith one implementation —LoanCalculatorImplIUserRepositorywith two implementations —UserRepositoryPostgresImplandUserRepositoryInMemoryImplIAccountingServicewith one implementation —AccountingServiceImpl. It depends onIUserRepositoryandILoanCalculator.- An HTTP server exposing RPC API.

We wrote a test for IAccountingService, then wired our test with LoanCalculatorImpl and UserRepositoryPostgresImpl.

Is it an integration test? It seems like it is. It involves several components of our program and talks with the database. Is it a functional test? Maybe. It’s checking whether an important service of our system conforms to a specification. Is it a unit test? Maybe - it checks the functionality of a system module.

Things get more interesting when we make our test abstract and add another implementation using UserRepositoryInMemoryImpl. So, should we continue to call it an integration test? It seems so. The test doesn’t talk to the database anymore but still involves several components. Is it still a functional test? Yes. Is it still a unit test? Yes.

But intuitively this new implementation is in many aspects better than the other one: most likely it’s faster, it does not require any preconditions (running database) to be met and there are fewer potential exceptions.

So, something important changed, but we may not know how to call that change. And our test taxonomy was useless.

Let’s build a better one.

The Constructive Test Taxonomy

Let’s assume that:

- We may assign an arbitrary amount of tags to a test,

- We have several predefined sets of tags

- We may assign no more than one tag from each set to a test — if we want more than one, the test may be split.

- We may establish a full or partial order on each of the sets and assign weights to the elements.

Let’s call such a set an “Axis” and try to come up with some useful axes.

Intention Axis

Each test is written with some intentions behind it.

Most common intentions are:

- To test some “specifications”, “contracts” or “behaviours” of our code. Let’s call such tests contractual,

- When we discover an issue in our code, we usually write a test confirming it, fix it, and keep the test as a regression test.

- When we know the problem but cannot fix it due to a design issue, a broken external library, or whatever else, we may write a progression test confirming incorrect behaviour (this type of test is very underestimated).

- When we need to check the performance of our code, we write benchmarks.

So, our first axis is called “Intention” and has possible values { Contractual | Regression | Progression | Benchmark }.

As a default guideline, we may say that Contractual tests are more important than Regression tests, Regression tests are more important than Progression tests, and in most cases Benchmarks have the lowest importance. So we may introduce weights for the axis points:

Intention = { 1: Contractual | 2: Regression | 3: Progression | 4: Benchmark }

Encapsulation Axis

A test may test just interfaces not knowing anything about implementations behind them. We may call them Blackbox tests.

Whitebox tests may know about implementations and check them directly (sometimes even breaking into some internal state to verify if it conforms to test expectations).

Blackbox tests do not break encapsulation and can survive many refactorings because of that. It’s a very important property, so we should always try to write Blackbox tests and avoid Whitebox ones at all costs.

Other tests may use only interfaces, but also verify some side effects (for example, a file created on disk) that cannot be, or are hard to, explicitly express. Let’s call them effectual tests. We may write them, but it’s always better to avoid them when possible.

Now we may define our “Encapsulation” axis:

Encapsulation = { 1: Blackbox | 10: Effectual | 100: Whitebox }

Whitebox tests are very expensive, so I’ve assigned them a high weight.

Isolation Axis

Some tests check just one software component. It may be a single function or a single class. These tests have the best issue localization possible. We may call them atomic tests because they check one unsplittable entity.

Some tests may involve multiple software components but do not interact with anything outside the program. So they test “aggregates” or “groups” of our entities, and we may call them group tests.

Some tests may communicate with the outside world (databases, API providers, etc.). So we may call them Communication tests. Such tests are usually less repeatable and slower, and should be avoided when possible.

Now we may define our “Isolation” axis:

Isolation = { 1: Atomic | 5: Group | 100: Communication Good | 1000: Communication Evil }

Different kinds of Communication

We may notice that there are at least two important Communication test subtypes. What’s the difference between a test calling a Facebook API and a PostgreSQL database? We can control and restart a database, but we can’t do anything with Facebook. Tests that interact with something outside the developer’s area of control are the most expensive ones and a pure source of pain. We call them Evil Communication tests.

The tests which do not interact with something beyond our control may be called Good Communication tests.

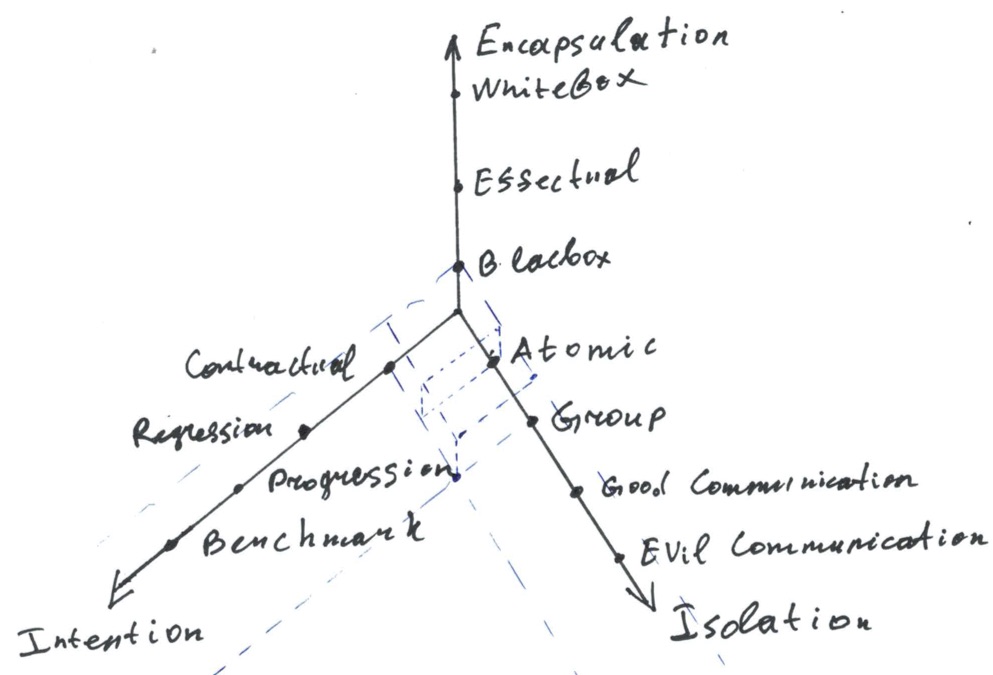

Test Space

Now we have several axes, so we may build a multidimensional “space” consisting of at least 3*3*4=36 test classes. Also, we may use the “distance” to the zero point as a simple scalar metric allowing us to roughly estimate which tests are “better”.

Two blue boxes near the “zero” correspond to two test classes having the highest value for us — “Contractual-Blackbox-Atomic” and “Contractual-Blackbox-Group”.

Also, you may try to use the following pseudo-formula to roughly estimate your maintenance costs associated with a test:

MaintenanceTime ~ (Encapsulation_Weight * Atomicity_Weight * Intention_Weight) / √(coverage)

Your very own axis

Taxonomies are hard and it’s not so easy to build a perfect one. The one we propose is not perfect either. You may give it a try; it’s useful. If you are unhappy with something, nothing can prevent you from adding your own axes or altering the ones presented in this post. Every team and project has its own needs and workflows so it may be a good idea to tailor a proper vocabulary for your specific needs. A proper test taxonomy may make a very useful guideline, help establish good practices and reduce maintenance costs. Just try to be precise and don’t forget to make guides and notes.

Ideas and observations

- All of the axes miss the zero element. What would correspond to it? Contracts expressed in your design and types. When your system does not allow incorrect states, there is nothing to test and maintenance cost may be nearly zero (or maybe not; it may be hard to extend a system with rigid contracts specified in types).

- You may document your tests adding abbreviations corresponding to the test type. For example “CBG” may stand for a “Contractual-Blackbox-Group” test.

Our reader from lobste.rs proposed a couple of interesting alterations to the taxonomy:

- We may add “Mutability” axis,

- We may change “Isolation” axis to be more precise:

Isolation = { expression | method | class | file | package | library | application | host | intranet | internet

Sounds interesting, we’ll try to give it a shot.

Modules, Dependency Injection, and better tests

Dual Tests Tactic

There is a simple but powerful tactic which helps us a lot:

- We design our code and tests to be able to test most of it through interfaces,

- We create a “dummy” or “mock” implementation for every single “integration point” — an entity which communicates with the outer world,

- For each abstract test, we create at least two implementations: one wired with production implementations, another one — with dummy ones,

- We skip “production” tests when they cannot be run (service is not available, etc),

- We try to isolate our integration points from each other and from business logic to avoid a combinatorial explosion in the number of possible configurations.

Such an approach helps you enforce encapsulation, allows you to implement business logic with blazing-fast tests, and postpone integration work.

Previously we’ve been doing it manually, and even in that case it was worth it. Now we have automated it.

Mocks vs Dummies

Many engineers love creating mocks using automatic mocking frameworks, like Mockito. Usually, when people say “mock” they mean “automatic mock.” From our experience, it’s generally a bad idea to use automated mocks. They usually work at runtime. They are slow. And what is truly important — they break encapsulation and rarely survive refactorings.

We prefer to create mocks manually (using in-memory data structures and simple concurrency primitives). We call them “dummies” to avoid ambiguity. We strongly prefer dummies to automatic mocks — they cost a bit more while coding, but they save a lot of maintenance effort.

An upcoming talk

A good module system and/or dependency injection framework may be very useful if you wish to make your tests fast and reliable. We are going to make a talk at Functional Scala regarding our bleeding-edge approaches to testing and how distage, our dependency injection framework for FP Scala may help you cut your development costs.

Conclusion

Sometimes it may be hard to design properly because we use outdated and imprecise vocabulary. It’s always a good idea to think freely and not be constrained by artificial legacy boundaries. The traditional testing approach and taxonomy are not perfect, and it may be a good idea to rethink them from first principles. In the end, you may notice that your code quality and team productivity increase and your design becomes more resilient.

P.S.

I would be happy to know your thoughts and ideas on the subject. You may contact me on twitter.